Early in December 1942 an ageing ocean liner slipped quietly out of the protective embrace of convoy ON149 and charting an evasive course, steamed away, unescorted, for the South Atlantic.

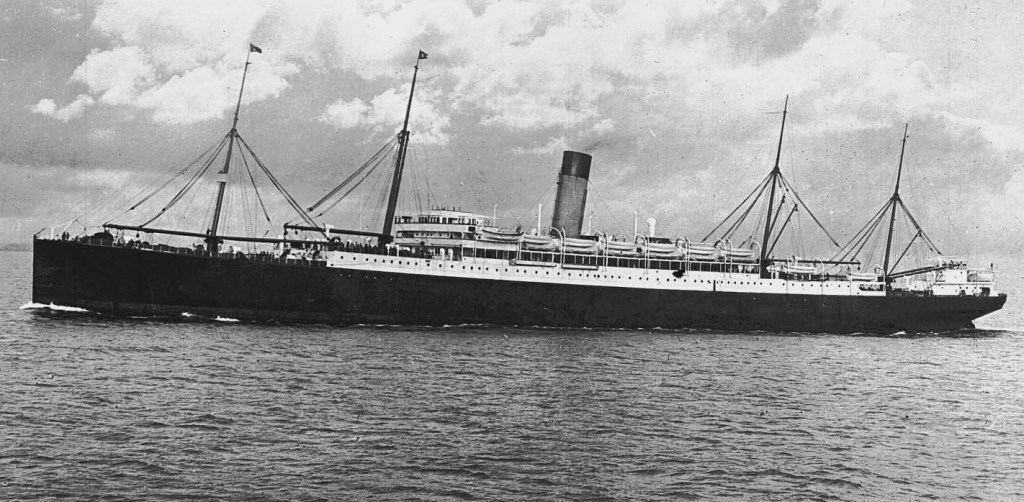

A contemporary of the Titanic – under construction as that ship embarked on her maiden voyage – this was the last and by far the largest of the Jubilee Class of British ‘long ships’. Designed to retain something of the elegance that reflected an earlier age of sail she still had a turn of speed considered a sufficient match for the U-boats. Sufficient, at least, that the Admiralty felt justified in authorising, perhaps demanding, a mixed complement of passengers both military and civilian.

Amongst the official count of 656 on board – crew, medics, families, children and combatants was one Captain William Logan Foster, a Merchant Navy Master with the Bibby Line. He was travelling as a passenger with an expectation of further instructions from the company’s agents. His recorded destination was Cape Town and it was understood he was to be taking command of a hospital ship.

Those instructions were never collected. On the evening of 6th December the first of several torpedoes was released by U-515. After taking a further two hits, the SS Ceramic was disabled but remained afloat. Despite worsening weather passengers were disembarked to life boats. Sometime later two more torpedoes were to sink the vessel. The following day U-515 was ordered to return to the scene to take the Master for questioning. Kapitänleutnant Werner Henke surfaced, surveyed the scene and recovered just one survivor for the records. Then every single remaining soul was left to perish as Henke submerged beneath the freezing waves with all lifeboats and rafts to be swamped and capsized, engulfed by the mounting storm.

Accounts vary; some have the submariners machine-gunning survivors in the water as they cried for help or repelling and throwing back those that managed to cling to the submarine’s hull. Others talk of a far greater number of lost lives. Propaganda and the need to manage morale played their part and official acknowledgement was delayed for weeks. In fact there were virtually no first hand accounts.

At a gathering some twenty years ago a few remaining crew members of U-515 were persuaded to talk. One had been on the bridge and reluctantly recalled events that even after sixty years left an emotional scar. Mountainous seas; the realisation there had been passengers on board; lifeboats flooded by waves, one with a woman holding a baby. . . Another wrote of the return; “cruising at half speed, sometimes faster” and the “terrible sight – lifeboats, wreckage and people”.

But what of the Kapitänleutnant? For an outstanding exponent of maritime carnage this was a prize – nearly twenty thousand tonnes to the tally. The U-boat commander with his hand picked crew, a roaming predator on a long leash; unseen, free of supervision; a competitive personal narrative in seeking and sinking tonnage largely untouched by incidental consequence. How did he feel when he surfaced amongst the desperate human detritus and was forced to confront the terrible evidence and harrowing extent of his handiwork?

In April ’44, U-515 was forced to the surface and Henke and most of his crew taken and held on the USS Guadalcanal. Subsequently he was incarcerated at a camp near Washington DC. Whilst there, in June of that year, he walked to the wire and started climbing, ignored calls to stop and was shot dead. It is suggested that, anticipating imminent defeat, he feared prosecution by the British for war crimes. This was effectively a suicide. The motive, though, remains speculation; lost with a mind that had felt compelled to execute acts that most would regard as cruel and abhorrent.

How is it that with centuries of insight, curiosity and creativity we still fail to manage those destructive instincts and conduct that only serves to visit anguish on our fellow humans? A wealth of understanding that seems to convey little other than the privilege of knowing witness to our own follies.

In the mid twentieth century, in part informed by the Nuremburg trials, there was a period in which various studies and experiments sought to better understand just how humans could be induced to inflict such abuse. The Milgram experiment (obedience) and the Asch experiment (conformity) both illuminated a compromised autonomy.

When at Christmas 1914 men emerged briefly from their trenches to sing carols, play games and share their common humanity; why did they then return to resume the mutual slaughter?

Why does a lawyer who likes to portrays himself as a dedicated family man with a love of outdoor activities with wife and children choose, and with no other justification than the demands of his client, to proceed with callous indifference for the family life of others and to casually blight the formative years of someone else’s child?

We tend towards a resignation to specious inevitability – “C’est la guerre”. But that’s no more than observation; it’s the refuge of those reluctant to question convention or acknowledge unpalatable choice.

“These (matters) are incredibly stressful (but) little I can say or do”; – the response when the CEO of a complaints body is confronted with the intellectual inadequacies and logical fallacies characterising their determinations. Or the dismissive shrug; “it’s the best we have” to the shortcomings in another service. But in both the incapacity resides with the respondent, not with the challenge.

Too often those in a position to make a difference, to hold institutions to account, are ready with spurious sympathy but offer no more than signposts around the status quo. Too few care to upset an orthodoxy that rewards with a starring role. Theirs is a commitment that abdicates personal responsibility to a beguiling narrative. Protocol, procedure and selective rationale will furnish the authority for failure, and inadequacy.

In a sense we’re all victims, trapped in our personal realities. We wear an identity born of genetic predisposition and early conditioning, sustained in playing a part borne by opportunity and circumstance. And it’s so much easier to stick to the script – for many the only realistic option. I don’t suppose those poor individuals lost in the mud and filth of the first world war felt they had much choice. The script was a given – play the part or risk the opprobrium of cowardice and suffer the consequences of desertion. So do your duty; lay waste to the fellow man with whom you held no animosity and cling to the narrative that applies a balm of legitimacy. But don’t look too closely – the tin might be quite empty.

Of course there will be those who find opportunity offers a role well suited to their particular disposition. For some, founding experience can generate a sense of insecurity, inadequacy or resentment. These individuals might seek solace in abuse and domination or an assumed superiority. They aspire to a position that sustains their fragile internal masquerade. But the singular dialogue with an inescapable external reality is vulnerable. Circumstances change, the fiction becomes unsustainable – for some a blessed relief, an opportunity for a rewrite; but for many an unbridgeable chasm will open.

Little wonder there can be such reluctance to relinquish the delusional narrative – a curated reality with complicit disregard for less amenable facts. It is this reassuring charade that justifies and absolves and serves to reduce contingent trauma to mere incidental inevitability.

So what of Werner Henke? It was suggested that he nursed a hatred for the British; another report that upon returning to the scene he was upset at the sight that greeted him. But whatever brought him there, his end for sure found him trapped in a narrative that now knew no other viable conclusion.

And what of the lawyer and his dedication to family life? Well that’s his family life; in his story you’re just a target, fodder for the fee. In his story you play no other part.

But why should we suffer the ignominy of a demeaning bit part in someone else’s drama; collateral to someone else’s adventure? However enlightened, the imposed narrative will militate against equitable coexistence. The shrug of resigned inevitability doesn’t cut it; there are always choices. The democratic ideal demands collaboration in the plot, true dialogue, all to hear and be heard. It’s a fragile ideal, it demands vigilance and protection from the malign monologue. The pathology spreads and thrives on blind indifference and self interest.

.

————————————————————————————————————————

Just a footnote.

I’m not sure what prompted me to revisit the Ceramic incident. I never met Captain Foster – my parents were awaiting the end of the war to start a family. But my grandfather’s existence was a tangible presence in those early years.

My mother’s childhood home seemed to retain something – a lingering suggestion of far-off and exotic places in a world once so much wider.

Artefacts and furnishings made in what was Burma and Ceylon and brought home in the hold.

An elaborate old wireless set with an image of the globe kept in the dining room.

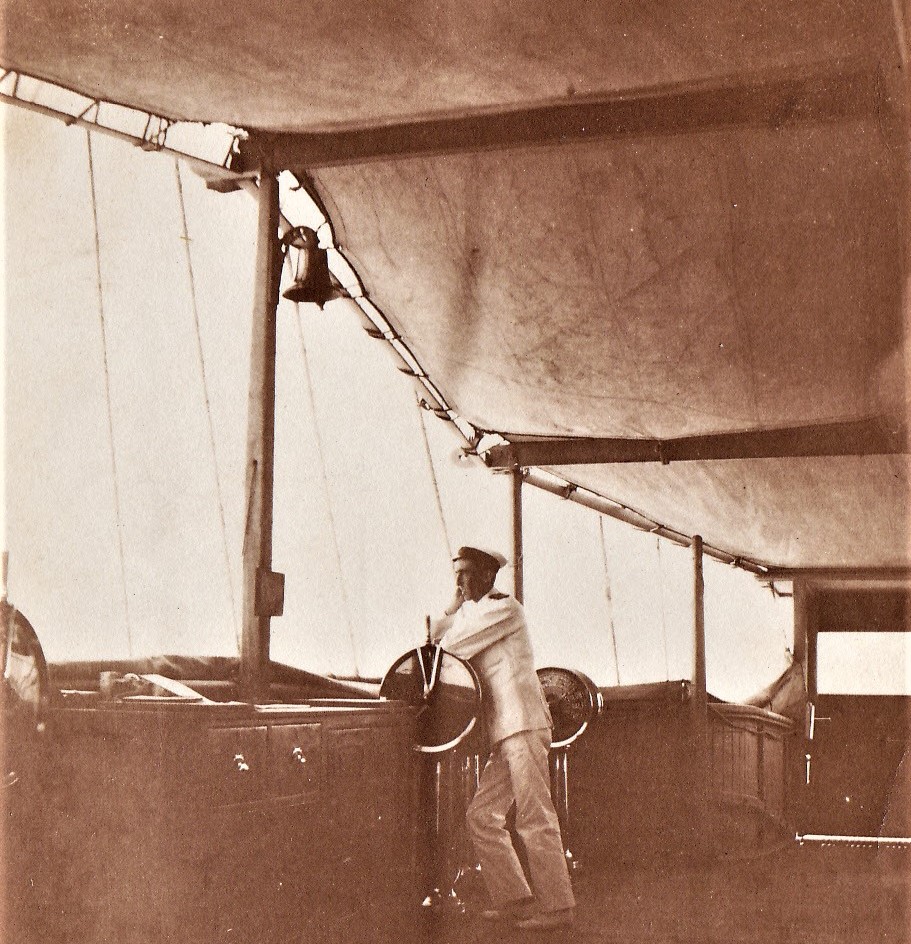

And there were the photos; images from another age: Shipboard visits from family and friends. Officers in tropical whites. The photo that never left my mother’s bedside.

And there are passenger lists and shipboard guides from colonial days. There’s the telegram posted to “Care Steelship Rangoon” in a 1936 announcement of my mother’s “highest matriculation”.

And there’s my grandfather’s last letter to his daughter as he boarded the Ceramic, the date punched out by the wartime censor.

All building a collective memory that contributed equally to a growing sense of self as any lived recall.

The war wasn’t spoken of in those days and I grew up with just the sketchiest knowledge and passing reference to the torpedo attack. It’s only very recently that I sought out the details and I have been taken by surprise at their emotional and very personal impact.

It’s painful to read; I find myself willing the Ceramic to make another evasive turn, the storm to abate, or for Henke to save the last two torpedoes and disable but leave a graceful old vessel afloat. Just to show some compassion; children, babies, mothers, fathers, grandparents; the whole panoply of human existence condemned to a desperate end. All that life; the joys, the intimacies; all those possible futures miserably extinguished for a trophy. A tragedy that feels distressingly close.

In the past I may have been somewhat dismissive of the effect of collective memory. I’ve been tempted to characterise actions designed to assuage historical hurt as empty political gesture. And doubtless there will be gestures, but it now feels inescapable that our sense of being transcends the confines of first hand experience. Our roots run far more deeply; they’re sustained on the resonance of countless fleeting moments.

Latitude 40 deg. 30 min. N. // Longitude 40 deg. 20 min W.

Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

A fascinating part of history. Hope to see more.

LikeLike